“Toska - noun /ˈtō-skə/ - Russian word roughly translated as sadness, melancholia, lugubriousness.

“No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases, it may be the desire for somebody of something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.” ― Vladimir Nabokov

The right word. Finding it is thrilling. It’s an unconscious chase we are always on. Even if we don’t realize it. Searching for and finding it matters.

The right word is not merely a better sign to more accuractl fundamentally changes the experience it points to. You become more attuned to it, more aware of its contours and shades. You’re better able to articulate it, in doing so, understand it.

Culture, media, conversations, lyrics, poems, and life constantly provide us with concepts and words to understand and communicate our experiences.

Searching for the “right word” isn’t just some tortured writer thing or puritanical academic obtuse nerdiness. Lacking a word or a concept, a gap in our shared conceptual resources can cause immense harm. In her work Epistemic Injustice the philosopher Miranda Fricker looks to understand how power and knowledge interact, specifically in cases of injustice. In chapter on Hermeneutical Injustice,

This provides a compelling case for understanding that the shared hermenutical resources (our shared tools for understanding and interpreting experience) is shaped by existing political power dynamics and that it can be changed by its users when experiences that may be unique to certain groups are collectively shared and discussed. Not just to have a space to be heard, but to develop hermenutical resources that they can use to navigate their unique

looks at the relationship between knowledge in power, she speaks specifically about the case of women in the of the concept of sexual harassment.

At the most significant level, the language we use to understand ourselves (wheather through an inward or outward-facing narrative) is shaped, and framed by the language we have (or lack). Language in this sense is self-forming.

How do you notice the absence of something you are not sure even exists? That’s the perniciousness. Especially when there is a vested interest of a certain

She asks the question: what concepts am I lacking to flourish fully?

“Jugaad”- (जुगाड़) And there are no

How we use it to understand ourselves and connect with each other is How we carve up reality. We also get to change how we carve it up.

Finding better words and using language more intentionally is one of our greatest expressions of agency.

Graveyard: That “and” in the previous sentence suggests a sequentiality I don’t want. We understand by communicating and communicate by understanding. An idea about language

- While I am not convinced of the truth of Wittgenstein’s “the limits of my language are the limits of my world,” I see it as an invitation. If language limits are one of the limiting factors of my “world,” my response: “expand it.”

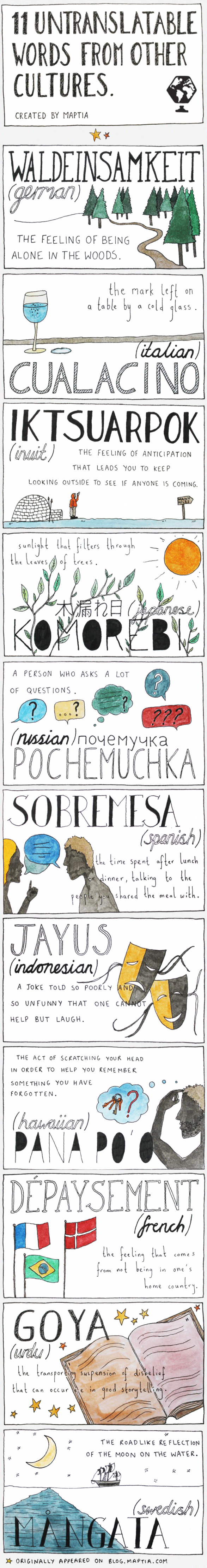

So often, I ask friends who speak a language other than English: what is your favorite word from your language that you feel loses much of its essence when translated into English?

The “shades of meaning” are only real in context.

As someone who grew up between the US and India, in the habit of picking the best of the cultures without fully identifying as one, I feel equipped inside enough, but also outside to explain the word and why its one of my personal favorite features of Indian and my self identified Indians.

- I went back to India for the first time in over two years. By god did I miss driving there.

It’s one of those words you can’t fully translate into another language, that tell you so much about the culture and people.

Driving in India feels like juagaad. It is the ability to assess in a moment how a system works, assess reality, and act out the best way to accomplish your goal.

-

Sometimes (as I learned over my summer living in Germany) the best jugaad is no jugaad.

-

Much like the trickesters in world culture, jugaad is somewhat amoral. Its amoral in part because of the utility. Often the time for jugaad in a situation is instantaneous. On confronting a situation, you have to quickly, almost immediatley asses. Who is this person in front of me? Are they new? Old? On a power-trip or meek?

-

I think this amorality cuts both ways.