When you enter the nineteenth-century European paintings and sculpture room in New York’s sprawling Metropolitan Museum of Art, an intimate, nude male bronze cast statue greets you.

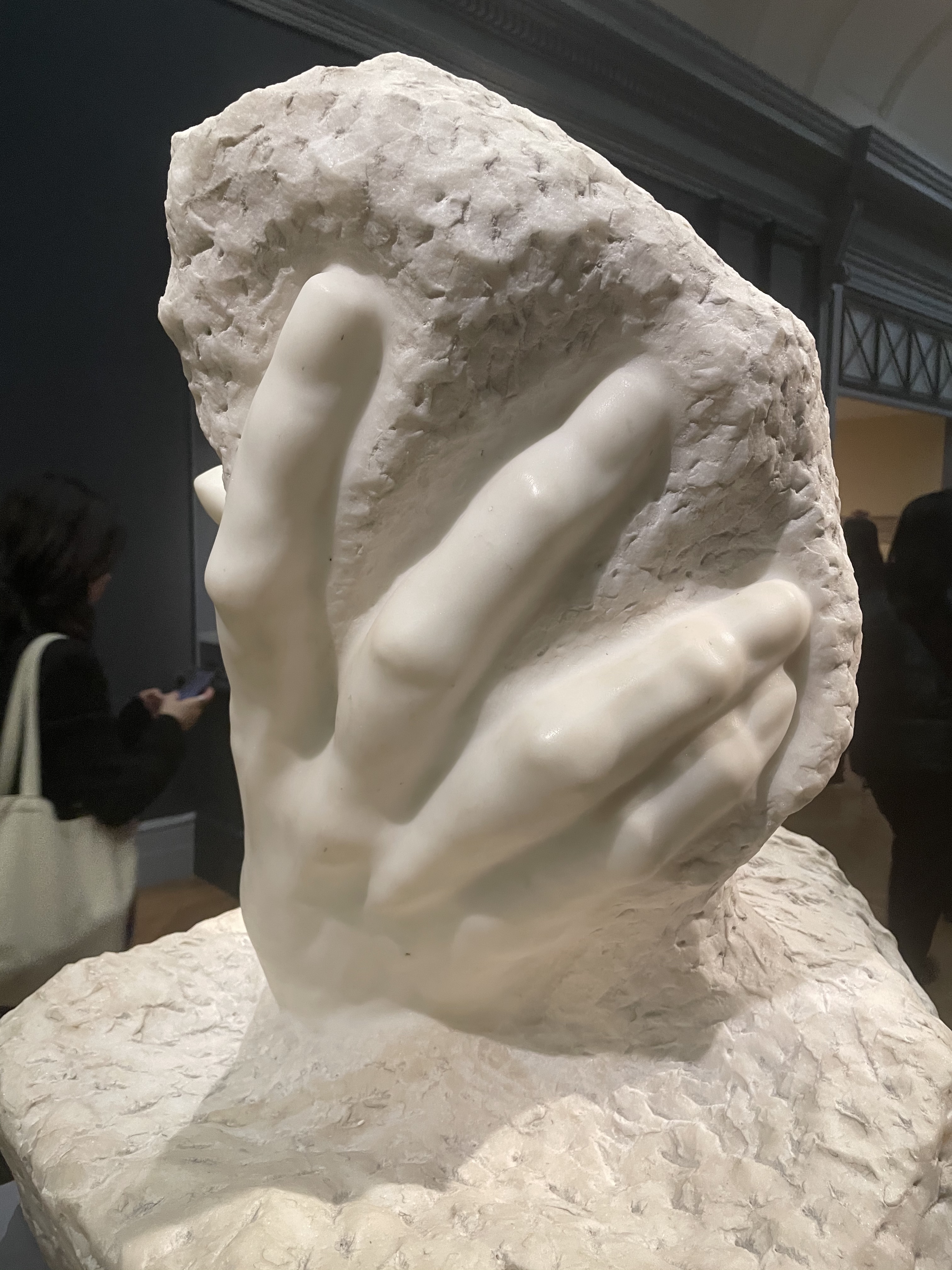

To the right of entrance a large, marble, smooth hand protrudes from a rough, circular marble base. Rodin’s In The Hand of God, is also intimate, Adam and Eve are locked in an embryonic embrace, but the mixture of rough uncut marble with the smooth, a distinctly Rodin style, is strikingly primitive as compares to the bronze statue. It depict the primordial moment of creation. The plaque reads:

“[T]he inchoate figures of Adam and Eve [are] cradled in God’s hand. The composition is an homage to his revered “master” Michelangelo, the Renaissance artist whose unfinished figures materializing out of rough stone symbolize the process of artistic creation. In this work, Rodin boldly equates the generative hand of God with the ingenious hand of the sculptor.” (Figure 1)

Up to the right, against and parallel to the wall, is another Rodin sculpture. Understated in relation to God’s hand but strikingly erotic. Eternal Spring also depicts an abstract female and male figure locked in a kiss. The statue according to its plaque is about “sensuality and impassioned lovemaking” and depicts the intimate, vulnerable, and “willful surrender” (Figure 2)

Up to the right, against and parallel to the wall, is another Rodin sculpture. Understated in relation to God’s hand but strikingly erotic. Eternal Spring also depicts an abstract female and male figure locked in a kiss. The statue according to its plaque is about “sensuality and impassioned lovemaking” and depicts the intimate, vulnerable, and “willful surrender” (Figure 2)

Both of these marble sculptures were carved in 1907 portray two distinct acts of creation — one divine and one human. Here I will considered together these two statues together and use them to reveal Rodin’s nuanced portrayal of eroticism, vulnerability, and identity in the human creation.

After lingering (for a suspiciously long time), I noticed a pattern that MET goers follow in their approach and viewing of Eternal Spring. After circling the Hand of God several times, pausing to read the plaque, they were drawn to Eternal Spring. Like satellites leaving the gravitational pull of one body to orbit another, they approached Eternal Spring along a diagonal. Met by the outstretched hand of the male figure, much smaller than God’s, reaches forward out of the sculpture. It forms the top half of an ‘S’ that is horizontal, slanted forward, and diagonal in space. The man’s hand creeps behind the uncut marble wing and grounds the eye’s journey along his arm, and continues over his head arm along the female’s arm wrapped around her curves, ending at her bare feet (Figure 3). Unlike the circular frame of The Hand of God, Eternal Spring is framed by a diagonal that is defined by a large ‘S’ shape along its level change. This ‘S’ figure is a staple of classical sculpture; indicating a full body. However, this dominating ‘S’ subverts tradition in its orientation and is formed by two bodies rather than one. Reminiscent of Raphael’s Disputa, Rodin uses different shapes and symbolism to distinguish elements of human and divine creation.

After lingering (for a suspiciously long time), I noticed a pattern that MET goers follow in their approach and viewing of Eternal Spring. After circling the Hand of God several times, pausing to read the plaque, they were drawn to Eternal Spring. Like satellites leaving the gravitational pull of one body to orbit another, they approached Eternal Spring along a diagonal. Met by the outstretched hand of the male figure, much smaller than God’s, reaches forward out of the sculpture. It forms the top half of an ‘S’ that is horizontal, slanted forward, and diagonal in space. The man’s hand creeps behind the uncut marble wing and grounds the eye’s journey along his arm, and continues over his head arm along the female’s arm wrapped around her curves, ending at her bare feet (Figure 3). Unlike the circular frame of The Hand of God, Eternal Spring is framed by a diagonal that is defined by a large ‘S’ shape along its level change. This ‘S’ figure is a staple of classical sculpture; indicating a full body. However, this dominating ‘S’ subverts tradition in its orientation and is formed by two bodies rather than one. Reminiscent of Raphael’s Disputa, Rodin uses different shapes and symbolism to distinguish elements of human and divine creation.

The individual elements of Eternal Spring are also shaped to build on the symbolism and help focus the viewer’s perspective. Each of the individual figures has its own ‘S.’ From the upward-facing feet to the hands of the female figure and the bent, crossed leg from the left body half of the male figure. Along the vertical axis where their bodies meet, there is a straight line from the meeting point of the lips to the male’s right foot rooted in the rough marble base. Finally, their jaws form the bottom of the circle, which continues through the female’s hand along his head. This circular shape formed at the head is identical to the faces in The Hand of God (Figure 3, Appendix). These shapes all help draw the eye to the focal point of the image — the kiss — and help to create the off-center diagonal perspective most viewers stopped at to view the statue. This position is perpendicular to the point where the female’s breast fills the contraction of the male chest (Figure 1, Appendix). From this view, the outstretched male hand invites us to view an incredibly intimate act. The MET’s image on the web fails to capture this view. It is too frontal, not respecting the diagonal dynamics of the frame. Had Rodin not invited us through his use of shape, it would’ve created a feeling of imposition rather than of invitation. We are invited to view from a particular perspective without shame or guilt. Unlike the Hand of God, which invites viewers to view divine creation from all angles, the passionate sexual act of human creation needs more careful framing.

The individual elements of Eternal Spring are also shaped to build on the symbolism and help focus the viewer’s perspective. Each of the individual figures has its own ‘S.’ From the upward-facing feet to the hands of the female figure and the bent, crossed leg from the left body half of the male figure. Along the vertical axis where their bodies meet, there is a straight line from the meeting point of the lips to the male’s right foot rooted in the rough marble base. Finally, their jaws form the bottom of the circle, which continues through the female’s hand along his head. This circular shape formed at the head is identical to the faces in The Hand of God (Figure 3, Appendix). These shapes all help draw the eye to the focal point of the image — the kiss — and help to create the off-center diagonal perspective most viewers stopped at to view the statue. This position is perpendicular to the point where the female’s breast fills the contraction of the male chest (Figure 1, Appendix). From this view, the outstretched male hand invites us to view an incredibly intimate act. The MET’s image on the web fails to capture this view. It is too frontal, not respecting the diagonal dynamics of the frame. Had Rodin not invited us through his use of shape, it would’ve created a feeling of imposition rather than of invitation. We are invited to view from a particular perspective without shame or guilt. Unlike the Hand of God, which invites viewers to view divine creation from all angles, the passionate sexual act of human creation needs more careful framing.

Once properly framed, however, Rodin does not shy away from portraying the dual nature of human creation as both carnal and divine. The woman’s lower half is prostrated, grounded, reminiscent of prayer, and her feet are fully exposed, a motif of vulnerability in Christological art. The linearity of her lower half contrasts and emphasizes the curvature of her upper half. The deep arch in her lower back heightens her sexual appeal by emphasizing her feminine curvature. Her pose is both erotic and sexual but also divine and vulnerable. Like the discomfort one can feel in extended periods of prayer, sex often includes poses that are also uncomfortable. But it is a discomfort that is forgotten. Though the pose is very clearly an uncomfortable one, it is self-aware in its framing, thereby conveying an authenticity that portrayals of eroticism so often lack.

This authenticity, in part, comes from Rodin’s style of leaving rough unsmoothed marble in his statues. Even in The Hand of God, he does not let us forget the materiality and earthiness of creation. Unlike Bernini, who obscures the materiality of his sculptures, Rodin highlights it. Man comes from God but is fashioned from the Earth. No act of creation, even the first, can escape this reality. So when the human figure is revealed by its contrasting smooth against the background of rough marble and emanates from the rough, we are reminded of where we come from. This honesty of materiality gives both of Rodin’s statues a texture of veracity, which then helps us view the sexual act without shame or guilt.

Rodin departs from this style of demarcation where the two figures meet. In both statues, they form a coextensive smooth surface. It is unclear where one ends, and the other begins; In Eternal Spring, the clear diagonal line serves as a non-boundary. Which, in addition to the abstractly rendered classical faces, connote a lack of identity. However, the conditions of the effacement are radically different. In The Hand of God, Adam and Eve don’t yet have an identity. They are “inchoate” in the embryo of God’s hand. Therefore their effacement of identity isn’t significant because they are innocent of identity. However, in the human act of creation, in all its sensuality and divinity, the loss of identity is “willful.” Just as vulnerability is meaningless if you’ve never been hurt, so too is loss of individuality when you have no identity. Similar to the bittersweet moment of the man’s fall in Milton’s Paradise Lost, it is only after Adam and Eve become aware of their nakedness and feel shame are they truly human. It is only after identity can willful effacement be meaningful.

It is on this question of what it means to be human I want to make my final observation. While so many elements of these statues are abstract, the most naturalistically rendered objects in both are the hands. In The Hand of God, we see, in great detail and at scale, the veins, micro-musculature, and texture formed by the folds of the skin of his hands. (Figure 4) He is drawing attention to the hands as creative tools. The plaque reminds us that Rodin “boldly equates the generative hand of God with the ingenious hand of the sculptor.” The hand, with its opposable thumbs, is our most distinct feature. Hands make artistic creation possible. This conceptual framing helps us understand the naturalistic hands in Eternal Spring. The female figure is gripping the male figure’s head, and his hand embraces her arm from behind. The detail of the hands is striking. This embrace is similar to the one in The Hand of God, but it is intentional and forceful. The man’s fingers are much closer together, indicating a tension contrasting God’s relaxed, spacious fingers. Combined with the earthy and honest style, the diverse role of the hands is brought to mind. We use our hands to work, fight and survive, but also to pray, paint, and caress.

Creation and identity are mutually constitutive, and hands are or medium for both. Hands and their products, more so than faces or bodies, are what distinguish us. They are our tools of demarcation from nature, which Rodin suggests through the mixed materiality of rough and smooth marble and the smooth human emanating from rough marble. Simultaneously they are what demarcates us from animals. God is defined by the creation of humans and by creation. Sex is both an act of creation and a symbol of what drives us to create in the first place. The non-boundary along the diagonal of the man and woman in both statues indicates this. However, in the non-naive human act, each figure has its own ‘S’ shape indicating a human identity and the ‘S’ they form together. Rodin’s incredible display of eroticism and “willful surrender” shows us that human creation requires a willingness to momentarily efface oneself, which can only happen if we dare to pose: erotic, prostrate, and all that is in between.

Images taken by the author at the MET, February 26th, 2023.

Images taken by the author at the MET, February 26th, 2023.